#

Learning How To Learn Programming: Notes on Teaching Programming with the Kernel Language Approach

These are some notes on Van Roy and Haridi’s Teaching Programming with the Kernel Language Approach” (PDF) outlining the pedagogy employed in the pair’s landmark work Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming. This ambitious book, known as _CTM, was published in 2004 by MIT Press 30 years after they published The Structure and Intepretation of Computer Programs, a book written by another pair of authors attempting to change the way people think and learn about Computer Science. I will walk through some of the key concepts of the paper, and hypothesize that the same techniques that the authors advocate for classroom use are applicable in professional settings, while asking an important question about the impact that commercial software development has on professional programmers’ understanding of Computer Science._

Bridging The Gap

The choice of what techniques to use in bridging the gap between the pure ideas of computer science and the realities of practical programming is impacted by the venue - the workplace, the classroom and the laboratory all have different needs. Van Roy and Haridi present “a new way to teach programming” that exposes and challenges the basic assumptions of typical classroom computer science education, with the goal of empowering the student with a strong grasp of underlying principles balanced by some experience with practical application.

The classroom is the first place many people get exposed to computer science and programming but many professional programmers are self-taught, and regardless of their pedigree, classroom computer science education is a scarce resource. Ultimately I’m interested in how the concepts that Van Roy and Haridi champion can be applied to professional programming. How can we harness the power of kernel language concepts and shine the light on the eternal question of “how computers work.”

“We present the kernel language approach, a new way to teach programming that situates most of the widely-known programming paradigms (including imperative, object-oriented, concurrent, logic, and functional) in a uniform setting that shows their deep relationships and how to use them together.”

“Widely-different practical languages…are explained by straightforward translations into closely-related kernel languages, simple languages that consist of small numbers of programmer-significant concepts.”

These two quotes sum up the what and the how of the kernel language approach. In terms of the kernel language itself, it is in fact its own programming language, a sort of “runnable pseudocode” that is executable in the Mozart/Oz platform.

At this point it is easy to indulge the “practical” part of your brain that says that there’s no point in studying a language that you can’t use in production. I often have to remind myself that I didn’t learn to program in a language that I ended up using in any professional capacity, and that many around me learned with an entirely different toolchain, an entirely different mindset, an entirely different venue. The point isn’t to learn a new language, it’s to learn new concepts, how to apply them, and how to draw conclusions about what paradigms are applicable to what situations based on that understanding.

Programming, As It Was Taught

According to the text, programming is typically taught in one of three different ways:

As a Craft - You learn one language, deeply. Its paradigms become the lens through which you learn everything practical and theoretical about Computer Science. Your knowledge and experience veer more toward the practical than the theoretical. You end up, for example, being an “Object Oriented Java Developer” or a “Functional Haskell Developer.” The authors criticize this method by citing an example of how the defects of a specific language or paradigm may excessively shape the thinking and practice of a student, e.g. believing that “Concurrency is hard” because “Concurrency in Java is hard.” This is how most professional programmers that I have met learned the language that they use professionally, and consequently how they have learned many concepts of Computer Science.

As a Branch of Mathematics - Your practical knowledge is superseded by a deeper understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of programming, typically limited to one language and paradigm. You are restricted in terms of practical application by the theoretical approach. The authors criticize this approach as narrow, citing semi-successful attempts by such luminaries as Dijkstra, but themselves aim to cover a broader range of concepts.

In Terms of Concepts - Your knowledge is concept first, typically taught with a programming language that, like Scheme, has “no syntax” and is as transparent as possible. Concepts such as logic, recursion, algorithms, etc. are covered. This approach, which the authors feel their work is most in line with, is also found in The Structure and Intrepretation of Computer Programs. Criticisms are leveled at the single language approach, lack of formal semantics, and missing fundamental concepts of their predecessors in this category, however.

Considering the pitfalls of the above approaches, the central question of the text becomes:

“How can we teach programming as a unified discipline?”

Because it seems apparent that teaching each separate concept through a representative language (some each of Haskell, Java, Erlang, etc.):

“…multiplies the intellectual effort of the student and instructor (since each language has its own syntax and semantics) but does not show the deep connections between the paradigms.”

My own personal computer science education history consists of:

- Attempting to learn concepts through programming languages instead of learning programming languages through concepts

- Attempting to learn paradigms the same “outside in” way

- A very rough understanding that concepts are inter-related through paradigms and programming languages

After many many years of the above, reading through the kernel language approach material in CTM made the syntax and semantics connections clearer, and also improved my understanding of the actual mechanics of the abstract machines that run them.

What Is The Kernel Language Approach?

After outlining the methods that they have observed, the authors make it clear that they want to communicate through concepts, to highlight the interface between the programmer and the raw concepts involved in interpreting and computing results from programs. In other words:

“In the kernel language approach, programming paradigms and their requisite languages are emergent phenomena”

This is a very powerful idea. It highlights the interconnectedness of programming languages by placing them on something like a continuum. Instead of using a practical programming language to learn concepts, you use concepts to learn programming languages. Not only programming languages, but their motivations, their design, the beauty in their structure. All that, and a reasonable intermediate representation to boot.

The essence of the approach is:

- Encode “programmer significant concepts” such as conditional statements, sequential execution, and concurrency in a kernel language which contains the correct combination of features for a given programming paradigm

- Extend this kernel language with syntactic sugar (more convenient interfaces to existing syntax) and functional abstractions (new additions to the language, new syntax) in order to make it more expressive and powerful

- Translate localized examples, algorithms, etc. written in the practical programming language to kernel language, and vice versa (great examples of translations of small pieces of Erlang code are shown in CTM)

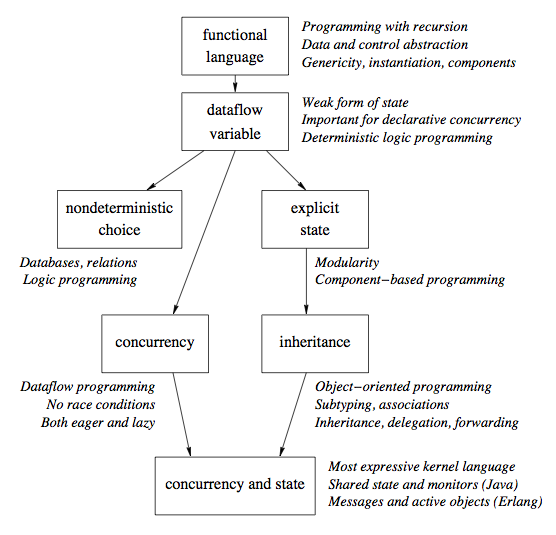

This diagram shows the steps for extending the initial kernel language to become more expressive by adding functional abstractions and syntactic sugar:

The simplest core of the language is functional. Various types of state are added, cautiously, as are concurrency, object systems, and more. The authors are very clear, especially with respect to state and concurrency, that these powerful concepts have to be added and treated seriously. In my opinion the semantics they lay out for each successively more complex language are very clear, insightful representations of the essence of what these languages can express. The progression from one kernel language to another is simple and easy to follow.

One of the more interesting sections of the paper is where the authors outline the approach known as the “Creative Extension Principle” that they use to systematize the means by which kernel languages are extended. They explain that they consider the simplicity of the semantics and the potential complexity of the resulting programs when determining when and how to add features to the kernel languages. This “layered” approach is very continuous and allows for a lot of different combinations of concepts.

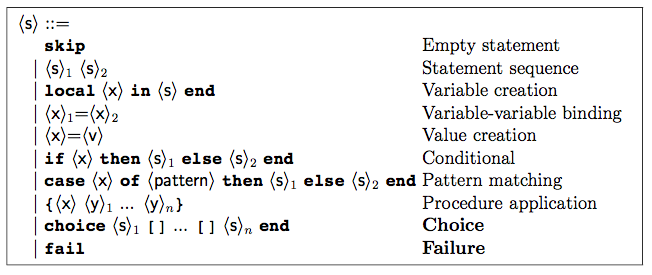

I thought I would include an example kernel language, in this case the language for relational programming, as presented in the CTM book. It’s not necessary to explain any of it here, and they don’t include it in the paper, but if you’re just experiencing these ideas for the first time, it’s nice to be able to see some context, so you can get a sense of the limited number of forms that the language has, of its capabilities syntax wise, and a basic sense of the semantics.

Teaching each of the concepts represented in the flow diagram, and showing how simple steps in combination can be used to actually “create” the syntax and semantics of new languages like the one above is the core of the paper’s message.

Because you can see very clearly how the interactions between the available operations work in a more correct, pure environment, you can apply that understanding when you write code in a practical programming language. For example, Van Roy and Haridi cite experience with students who knew how to program in Java with objects and state, but gained an actual understanding for how objects operate by using the kernel language approach.

From the Classroom to the Workplace

The authors do not concern themselves with many of the practical aspects of professional programming in this paper by virtue of the fact that they’re trying to explain their approach to concepts, not design. However the novelty of the kernel language approach does apply to at least a few different professional scenarios:

- The kernel language can give developers a common language to discuss algorithms when they may themselves specialize in different practical programming languages. It is not uncommon for Objective-C, Ruby, and JavaScript developers to work closely with each other, and discussing algorithms and data structures can be difficult because of the impedance mismatches encouraged by speaking in terms of one language or paradigm.

- The popularity of various programming paradigms tends to change over time. Functional programming is seeing a resurgence, for example, and transitioning developers from imperative Object Oriented paradigms to functional languages can be a challenge. The kernel language approach offers a potential transition point for these and other developers in a similar position.

- College students who want to work professionally in a field in which they did not get proper exposure during their coursework or internships can use the kernel language approach to gauge their competencies and forge pathways towards deeper understanding that crosses paradigm boundaries.

There is often an artificial line drawn between the professional and the academic, but this isn’t necessary. The formal aspects of the kernel language approach may seem intimidating at first but are very much digestible.

Conclusions

Many professional programmers jump straight into the most complex form of programming without exposure to the concepts the kernel language approach encompasses. This raises the question: are we limiting the potential of our workforce by limiting people’s exposure to one paradigm only? This causes a tremendous amount of churn and cognitive dissonance that doesn’t have to hold back developers as much as it does. My personally very slow, arduous journey towards making the connections between the various programming languages and paradigms (even those I have experience with) is a testament to the power of the potential of the kernel language approach.

Instead of hiring developers to write code in a specific language, we should encourage cross-paradigm movement and expose our developers to as many different concepts of Computer Science as possible. Those who know both broadly and deeply will have a better chance of forming the kinds of intuition that make for successful, productive programmers.

Thank you to @gordondiggs, @timonk, amd @eallam for your thoughtful and helpful reviews.