A Framework for SaaS Pricing

For many, pricing a product remains a dark art. Without a framework to work within, many people who create products simply copy competition, or just straight-up guess at what good prices might be. Talking to founders and startup executives who have struggled to get a grasp on how they should approach pricing has led me to search for relevant research on the subject, in order to be able to help them better. During this search I came across “Cloud Services Pricing Models” by Laatikainen, Ojala,and Mazhelis, which extends an existing framework for product pricing to be more specific and appropriate for cloud/SaaS software.

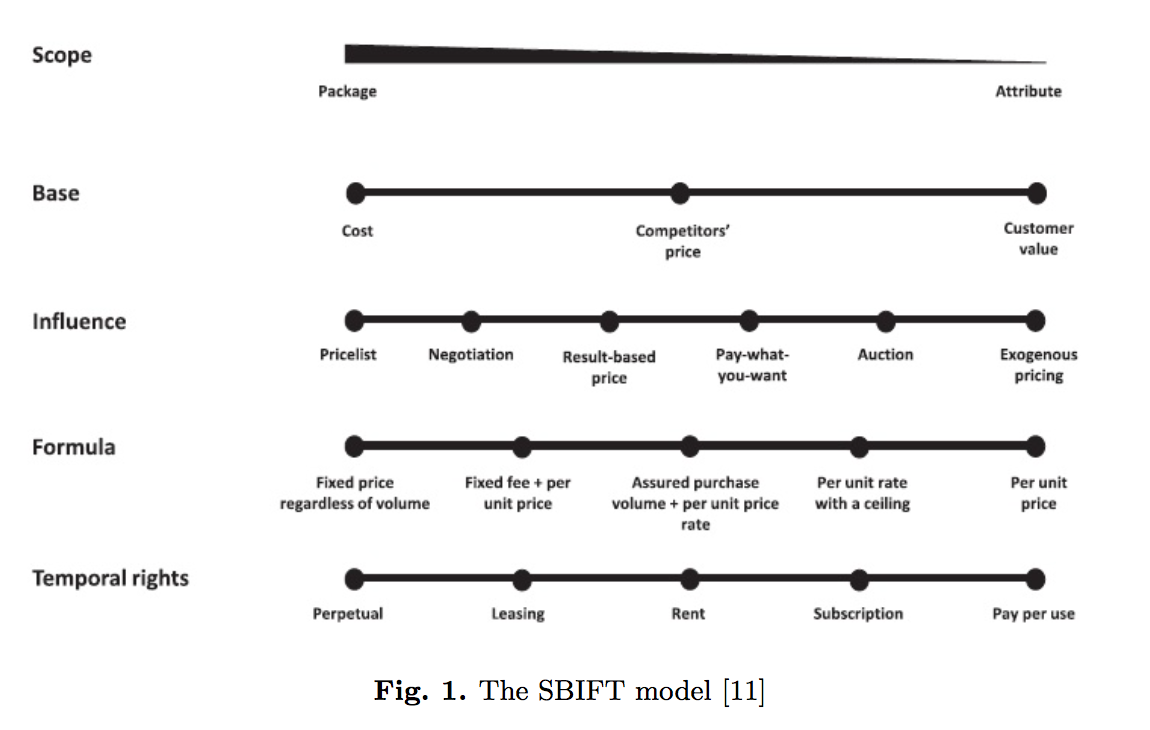

The existing SBIFT framework is named for the dimensions in the chart:

The idea is that a pricing model can be described by choosing a set of positions along a set of dimensions. Scope refers to the size of the product, base is the perspective that is most heavily used to inform pricing, influence describes various parties’ ability to control pricing, formula is another way of describing packaging, and temporal rights refers to the length of time a user can use the product.

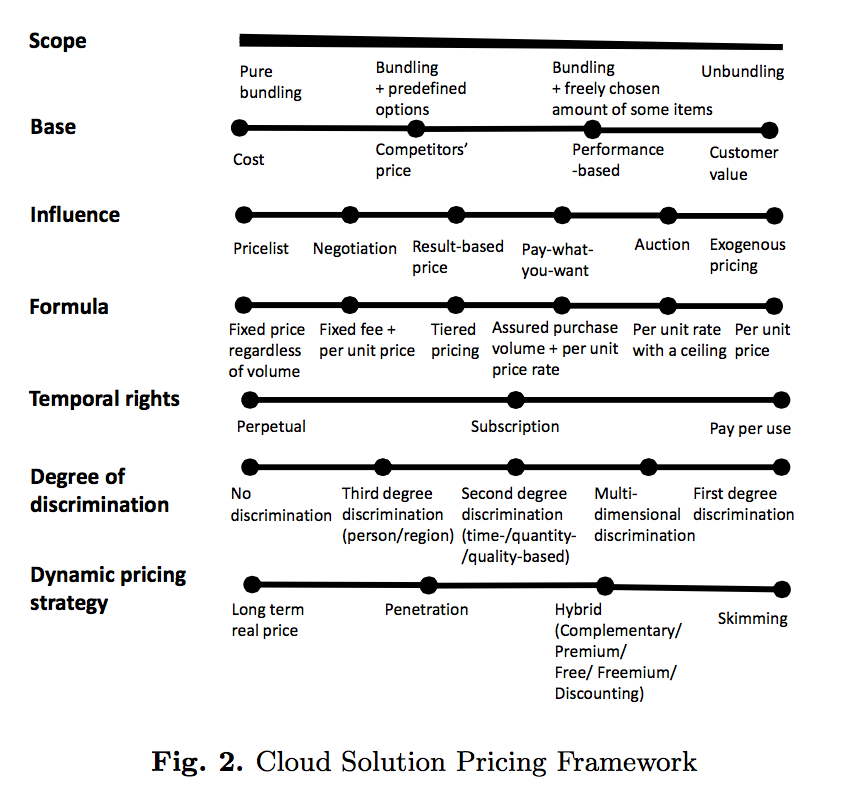

Starting with this model, the authors extend it to be more specific to pricing and selling cloud-based software services:

Scope changes to move away from language using “packaging” and “attribute” toward language that uses “bundling” and “unbundling,” which are more common terms in the SaaS domain. “Pure bundling” refers to software which is sold in a way where features are only purchasable in pre-defined bundles, and “Unbundling” refers to the opposite, where the scope of features can be dynamically determined. Performance-based pricing, or pricing that is based on a certain SLA, is added to the base dimension.

The formula dimension gets the addition of a tiered-pricing item, which is a widely used packaging mechanism is SaaS products. Subscription is added as an item in the temporal rights dimension, and other items are removed, vastly simplifying this dimension, which is also appropriate given common sense understanding of the way SaaS works. Pay per use is also added in this dimension.

The degree of discrimination dimension is added in this cloud-informed version of the SBIFT framework. The authors describe price discrimination this way:

“Price discrimination is used when the same product/service is offered for different buyers for different price. This strategy is extremely important for providers of digital goods, since the low marginal costs allow them to sell the offering also for customers with low willingness to pay.”

Essentially, discrimination describes a wide range of techniques (discounts, etc.) that companies can use to specialize their pricing based on the customer, the circumstance, or the offering.

Finally, the dynamic pricing strategy dimension attempts to capture the strategies that companies can use in the medium and long term to describe how their pricing might change. I recommend reading this great post by Tom Tunguz on pricing strategies for more context and information on some of the terminology in this dimension.

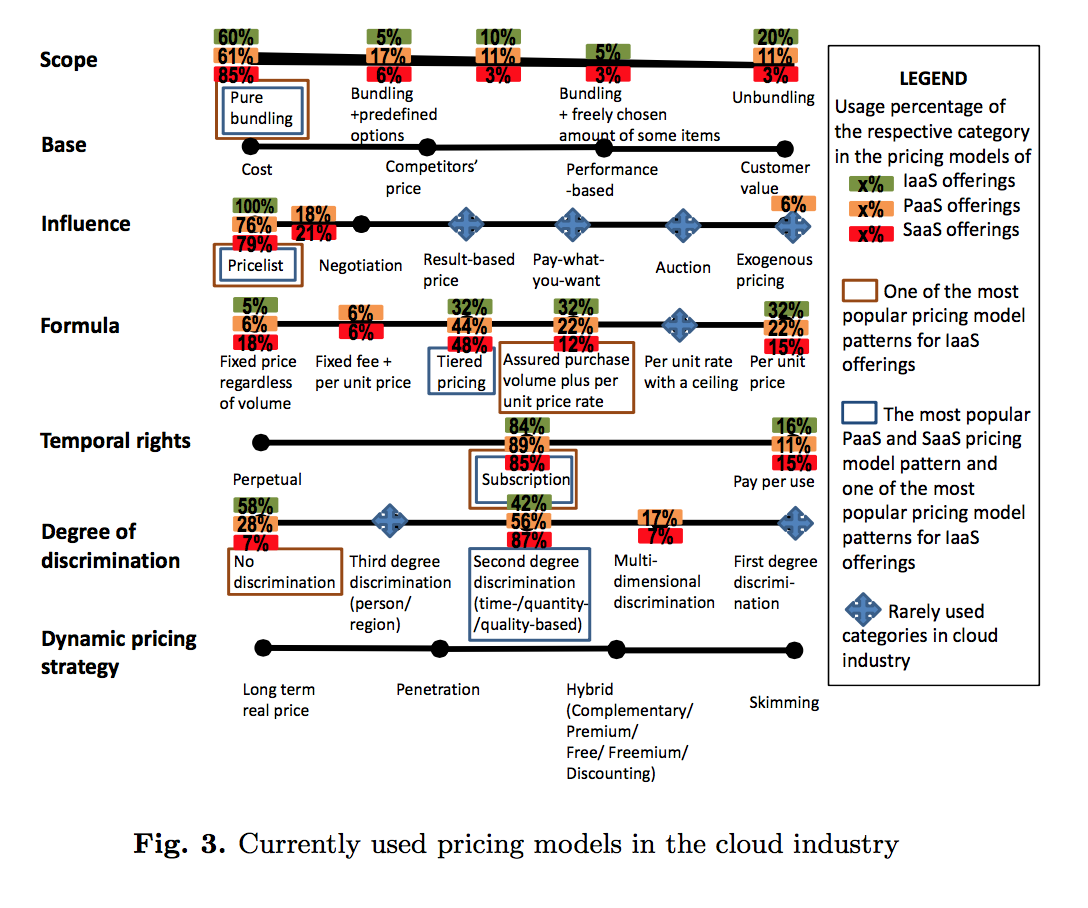

Once the model has been constructed based on research, the authors characterize the pricing implementations for 54 companies selling cloud services. These are divided into three groups, SaaS, IaaS, and PaaS, which serve to illuminate a few segmentation differences in the outcomes of the research.

Beyond the interesting takes on how to classify elements of a pricing framework, the paper’s real power comes when survey results are overlaid on top of this newly defined model:

Tracing through all of the elements aside from Base and Dynamic pricing strategy, which did not have enough data, you can see the choices that most companies make, segmented by sector: SaaS, IaaS, or PaaS. Popular choices in each dimension are highlighted with boxes, and otherwise segmented percentage breakdowns are offered.

There aren’t a ton of huge surprises in the breakdowns, but it is definitely instructive to see how the companies they researched actually are distributed amongst these different dimensions and items. An interesting exercise would be to pose as a question to someone what they thought these breakdowns might be, and then compare them to the research presented.

More than anything, the usefulness of this research is summed up best by this quote from the paper:

“In this research, we attempted to find a systematic way to describe the pricing models in order to help decision makers plan, develop and speak about pricing alternatives.”

For folks who are looking to demystify pricing in order to be able to speak intelligently about their decisions and those of their competitors, this is priceless. In working with companies who are started by technical people and market software to developers, it’s one of my missions to help technical people see marketing and sales as a science backed with frameworks that can help them understand their problems, much as they do with software. I think this model is a great step in that direction.