#

#

Why We Need Explicit State

The fact that the authors of Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming wait until page 405 (about halfway through the book) to introduce the concept and implementation of explicit state is a joke that tells itself. Explicit, mutable state is the cause of enough confusion and complexity that entire languages and paradigms are based around the idea of avoiding it, and yet many beginning professional programmers and computer science students learn with it up front. Unfortunately, in the long run, the joke is on these beginners, who often struggle in a sea of complexity.

“Explicit State” is the title of Chapter 6 of Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming. Far from a diatribe, the treatment of the subject is subtle in the hands of Van Roy and Haridi who use introducing explicit state as an opportunity to consider the pure world of declarative programming in the harsh realities of the real world.

CTM is a book that is distinguished amongst the Computer Science textbooks that preceded it in a variety of ways, from its early introduction to dataflow variables to its multi-paradigm approach. Certain aspects of this radical departure from previous literature at times seems like a direct reaction to certain books in particular, one of them being Abelson and Sussman’s epic The Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (SICP). Interestingly, in holding off on the discussion of state and trying to balance a description of its importance with warnings about its cost, the two books take very similar approaches. I’ll cover a bit of SICP’s approach as a way of reinforcing some of Van Roy and Haridi’s ideas in this post.

During the course of this tour of explicit state, the stateful model of computation is introduced, which bears a strong resemblance to the model used in Chapter 5’s message-passing model. A few different applications of the stateful model are discussed, including the implementation of Abstract Data Types, which see some very nice improvements over their declarative counterparts. Because complexity comes along with the introduction of new ideas to the computational model, ideas for handling it are discussed, and finally the fundamental challenge of the sequential nature of state is addressed.

What is State?

Before explaining the new techniques we have at our disposal, the authors want us to ask ourselves: What is State? Or maybe more specifically, What is a state?

“A state is a sequence of values in time that contains the intermediate results of a desired computation.”

The authors explain that there are two types of state - implicit or declarative state, and explicit state. We have seen implicit state before in the book, such as recursive functions that encapsulate values over time. However, the authors distinguish this type of state as implicit because the consumer of the function in that case is not concerned with the implementation detail as being stateful, it simply produces the desired computation.

Explicit state, on the other hand, is defined as:

“An explicit state in a procedure is a state whose lifetime extends over more than one procedure call without being present in the procedure’s arguments”

This kind of state wasn’t possible in other models that we’ve seen, and we have been warned repeatedly about the potential for complexity that allowing this semantics can introduce. Still, this type of programming with explicit state is ubiquitous and necessary, so understanding how it works is important.

The Stateful Model

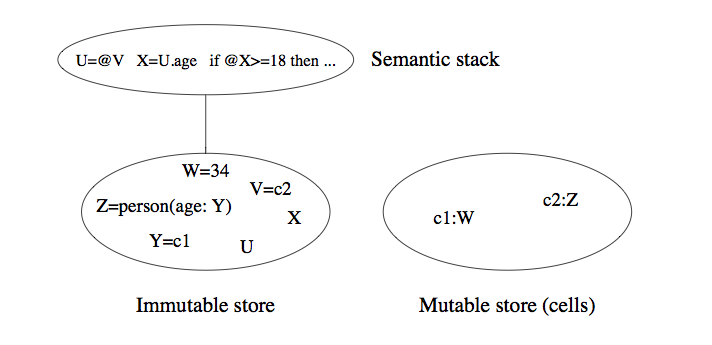

The stateful model is a tweak on the declarative model of computation that adds a mutable store alongside the immutable store and the semantic stack that we see in the most basic kernel language implementation:

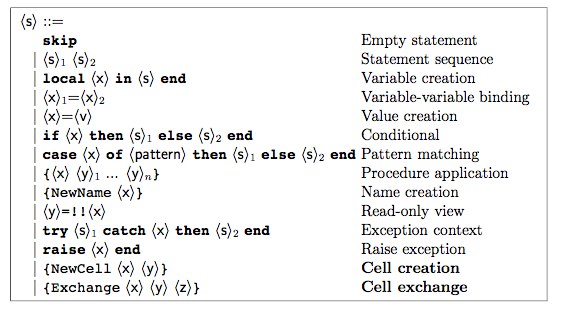

Stateful programs in this model are always sequential. The “Semantic Stack” above represents the ordered operations that comprise a program written in the kernel language. The “Immutable Store” is present in all of the kernel languages we have seen so far, and is the main “environment” which preserves the stated relationships between immutable variables and values. New here is the “Mutable store” which allow a new syntactic construct enabling a powerful semantic addition to the language: mutable state. This requires the addition of a minimal number of operations to the kernel language:

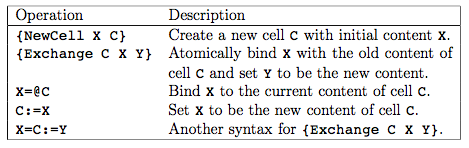

Two convenience methods for manipulating cells can make the language even more expressive, but amount to syntactic sugar for the Exchange operation:

With this new sematic device (the mutable store), we can create, assign value to, read value from, and swap the values of the contents of mutable cells. Here is a simple program that uses these new constructs:

local

C ={NewCell 0}

in

fun {SumList Xs S}

C:=@C+1

case Xs

of nil then S

[] X|Xr then {SumList Xr X+S}

end

end

fun {SumCount} @C end

endHere we can see a new Cell being created and used within the scope of a function. Repeated calls to SumList in the program will encapsulate the state of the Cell, allowing the consumer of the function to worry only about the value, and not the implementation details of the function.

This is the essence of the power available to us, and the reason that almost every practical programming languages is willing to pay the cost of introducing a technique that requires a radical rethinking of the implementation of the mechanics of computation.

One way to think of it is that as we “don’t care” about the implementation details of the SumList above, we also don’t have access to change it in a fundamental way. This tradeoff is something that is very well covered in Abelson and Sussman’s treatment of the same topic, so I’m going to take an opportunity to indulge a tangent in that direction.

The SICP Perspective

SICP is a book which is primarily concerned with teaching functional programming through the use of the Scheme programming language. Similarly to CTM, it spends a lot of time explicating the mechanics of computation, but through the lens of one paradigm, and primarily from a mathematical perspective. To best teach those that understood engineering and mathematical principles and get them to understand computation, the approach is taken to begin with functions that are pure, and to work from there. This probably sounds familiar if you’ve read the other posts on this blog about CTM.

To highlight the elegance of a bit of well-placed explicit state, the authors of SICP ask us to consider a random number generator and the use of that kind of function in a larger program, like a Monte Carlo simulation. Without explicit state, the following random number generator, written in Scheme, would not be able to provide the nice interface of just calling rand:

(define rand

(let ((x random-init))

(lambda ()

(set! x (rand-update x))

x)))Instead, you would have to pass the current value of the random number generator each time, which quickly becomes a pain in even a trivial program like the one the authors demonstrate.

To get a sense for the fundamental change that takes place when SICP introduces the set! operation, it is important to realize that up until the point in the book where state is introduced, one mechanic (the substitution model) had been used to compute programs. This model has the same declarative, referentially transparent properties as the early models in CTM.

The authors of SICP are quick to praise the transparency and simplicity of the substitution model, and once state is introduced, they wax poetic about its loss. The following quote is from a lecture series the authors gave using SICP as a textbook. After demonstrating how encapsulated explicit state can behave as the function above does, Sussman relates that:

“And what we see is the same expression leads to two different answers, depending upon time. So demo is not a function, does not compute a mathematical function. In fact, you could also see why now, of course, this is the first place where the substitution model isn’t going to work. This kills the substitution model dead.”[3]

Anyone who has struggled with understanding why they find imperative programs so complex, especially at medium or large scale, should review the transitions in these two books to help them put a finer point on their understanding. Seeing the authors of two prominent texts articulate this idea so clearly, that complexity comes along with state and that state is a function of time was a revelation.

One aspect of the use of set! in Scheme that Sussman highlights can be seen in the following implementation of a factorial function that uses explicit state internally:

(define (factorial n)

(let ((product 1)

(counter 1))

(define (iter)

(if (> counter n)

product

(begin (set! product (* counter product)) ;; Assignment 1

(set! counter (+ counter 1)) ;; Assignment 2

(iter))))

(iter)))What Sussman highlights is that when writing this program, the programmer is forced to make the decision for what order to assign the variables in, as shown in the lines labeled Assignment 1 and Assignment 2 above. If you switch the orders of these two statements, which would preserve the semantic meaning of the program (what you want to do is set the product and increment the counter, the order is meaningless).you will introduce a bug. And as Sussman states:

“It’s a bug that wasn’t available until this moment, until we introduced something that had time in it.”[3]

I thought this was a fascinating way of stating what is at the heart of the complexity of large imperative programs. After Abelson and Sussman introduce this bug, in the footnotes of the textbook they write:

“In view of this, it is ironic that introductory programming is most often taught in a highly imperative style. This may be a vestige of a belief, common throughout the 1960s and 1970s, that programs that call procedures must inherently be less efficient than programs that perform assignments. (Steele 1977[4] debunks this argument.)”[5]

Tracing the preference for educational choice to decisions made based on uninformed understanding of computer architecture is probably too good to be true, but it is an interesting question, and one worth thinking about more - what does the tendency towards imperative programming languages in educational contexts buy us?

Abstract Data Types

Abelson and Sussman’s idea, that we pay for the costs of explicit state because it makes certain other aspects of practical programming that much more elegant and potentially modular, is echoed in CTM’s coverage of Data Types (ADTs), or “a set of values together with a set of operations on these values.” The authors had covered ADTs earlier in the declarative model, and demonstrated that there are various properties, such as openness and security, that define how a programmer interacts with instances through their interfaces. With the stateful model, however, things have changed:

“Now that we have added explicit state to the model, we can present a more complete set of techniques for doing data abstraction.”

There are eight ways to organize a data abstraction according to the book’s formulation, and many of them are demonstrated. A simple stack data structure is presented in the declarative style and then shown in other variations until the stateful version is shown. In all cases the stateful version looks like the modern practical programmer’s idea of an ADT, with a proper interface and knowable performance characteristics.

Polymorphism as it comes to operating on ADTs and parameter passing in the stateful model are covered, wherein the ideas of the costs and benefits of state are thoroughly examined. After all of these topics are under our belts, we get introduced to some nice implementations of “Stateful collections,” which are of great interest to modern programmers, who tend to prefer maps to lists.

Tuples, records, arrays, and dictionaries are designed to meet a common interface for access and setting content and position where appropriate. It is once we can encapsulate values within data type objects and make them conform to common interfaces that we really see the promise of explicit state. When well contained, it is indispensable, and though it would be nice to never need it, because everything would be declarative, we know that that just isn’t realistic.

Reasoning With State

After discussing the potential pitfalls of the stateful model, Section 6.6 discusses some ideas for tools that can be used to reason about stateful programs. The reason this is necessary is summed up nicely here:

“Programs that use state in a haphazard way are very difficult to understand. For example, if the state is visible throughout the whole program, then it can be assigned anywhere. The only way to reason is to consider the whole program at once. Practically speaking, this is impossible for big programs.”

Invariant assertions are introduced as a way to get back some of the transparency that comes with reasoning about declarative programs. The idea is that each operation associated with a data structure (as in any of the ADTs discussed above) would have pre- and post-conditions specified. These specifications would serve to bolster the design of the system and how a programmer can come to understand what its goals are. The fact that they are separate from the implementation is touted as an advantage that decouples the interface from its code. Assertions like this have been seen in the Eiffel programming language amongst others, and the possibilities of extending popular dynamic languages with these capabilities is worth exploring.

To offer a higher level of abstraction for reasoning about programs, proof rules for the stateful model (without aliasing) are shown, which is an intense read that I am still trying to form an intuition for. In one of the admittedly most gentle intersections of mathematical proof notation and computer science theory I’ve come across, the authors show the proof rules for binding, assignment, procedures (with and without external references) and loops. Doing this, they have built a sound foundation for formal reasoning with respect to the operational semantics of the kernel language. New concepts can be invented, proof rules created, and so on, and the authors state that this can be a means of reasoning about stateful programs. The interface for this is unclear to me, and I’ll need to do some more reading to really grasp at what level of abstraction it is supposed to be applied. Nonetheless it is worthwhile for how rules for one statement can be applied to others to form an intuitive system of related operations.

A Reason For State

The authors end the chapter with a pair of warning statements:

“The real world is parallel”

“The real world is distributed”

Both of these present challenges to stateful programming because of its sequential nature. If bringing this up under the heading of “A Reason For State” seems odd, my point is that these notions help us put a finer point on when we need to use state and how we should use it.

Programming languages that embrace distribution, like Erlang, naturally have a better handle on how to encapsulate state than languages that don’t. The process abstraction in Erlang, like the message passing model discussed in an earlier chapter of CTM, is an example of how we can isolate state in a way where reasoning about it becomes simpler, so you do not in fact have to “hold the whole program in your head.” Of course in practice this is difficult because programs in any language can be written in complex, order sensitive ways that defy logic, and so we must press on and continue to develop tools for reasoning about programs.

The practice of examining what state is and why we need it is a fundamental component of understanding practical computation. We have seen bits of state here and there, encapsulated in lazy computation, in message-passing concurrency, etc. The idea of understanding all of the complexities that state introduces is not to search for a way where it isn’t necessary, but to search for a system where dealing with it is tractable. One goal for modern programming languages is to create a system where applying explicit state where it is not necessary would not be an attractive or “easy” way of solving a problem.

State is a fundamental component of how we reason about computation and thus the tradeoffs we accept are worth it in the long run. How we introduce it into our programs can be positively impacted by a deeper intuition for how it works and how it got there in the first place.

Works Cited

All quotes unless otherwise cited from Van Roy and Haridi. All Scheme code above from [5]

[1] Van Roy and Haridi. Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming MIT Press, hardcover, ISBN 0-262-22069-5, March 2004

[2] Abelson, Harold and Sussman, Gerald Jay. Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs Lecture Series 5A: Assignment, State, and Side-effects Available online here

[3] Eric Grimson, Peter Szolovits, and Trevor Darrell, 6.001 Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, Spring 2005. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed 12 02, 2013. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike. PDF Of Lecture Transcript

[4] Steele, Guy. Debunking the ‘Expensive Procedure Call’ Myth, or, Procedure Call Implementations Considered Harmful, or, Lambda: The Ultimate GOTO MIT AI Memo #443 PDF available here

[5] Abelson, Harold and Sussman, Gerald Jay. Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, second edition. MIT Press, 1996. Available online here.