# #

Distributed Systems Archaeology, Part Three

This post presents the final part of a narrative form of the talk I gave at Ricon West 2013. Part one can be found here and part two can be found here. The works cited can be found here, and the slides can be found here. Video is forthcoming.

The Market

The impact of commerce on distributed systems research

So far we’ve discussed the philosophical and humanity-based origins of distributed systems research in the work of Licklider, Minsky and Hewitt, and the formal origins in the work of Dijkstra and Lynch.

One of the motivating factors in my decision to study distributed systems more deeply was that I needed to understand how they worked better in order to be professionally competent. From this I can extrapolate (not that I have to, people are complaining about this constantly) that many other developers are in similar situations, suddenly finding themselves interacting with distributed systems as their projects grow, or simply as they have the realization that they have in fact been distributed systems programmers all along.

I think the existence of this conference alone proves that there is great commercial interest in distributed systems in 2013, so an interesting question came to me - has this always been the case?

There were few explicit commercial applications in Minsky and Hewitt’s work, and though it could be argued that Licklider’s money from DARPA that helped to create the lab at MIT did come from somewhere, by all accounts, researchers were free to explore at a time when things seemed new, fresh, and possible. Dijkstra and Lynch also published at the fringe of commercialism for a long time, focusing on the formal and mathematical underpinnings of the field.

I was very happy to find, however, that someone I was very intent on studying, Leslie Lamport, did have very interesting interactions with industrial work on distributed systems early on. As I mentioned before, author’s web pages with lists of published works are goldmines for researchers, and it is worth nothing that Lamport’s deserves to be in the world wide web hall of fame for his. It is amazing.

Amongst the many gems on Lamport’s page is a paper from 1978 called SIFT: Design and Analysis of a Fault-Tolerant Computer for Aircraft Control. Lamport annotates this entry with the following quote:

“When it became clear that computers were going to be flying commercial aircraft, NASA began funding research to figure out how to make them reliable enough for the task.”

Part of that funding was the SIFT project, which was charged with the task of designing the hardware and software for the aircraft and formally verifying its correctness. Lamport explains that the technology described in this paper is notable because the distributed system that composed the airplanes hardware and software could tolerate malicious, also known as Byzantine faults.

In 2003, Lamport published High-Level Specifications: Lessons from Industry, a collaboration with an intel engineer he worked with to formally verify multiprocessor memory designs. Lamport has applied techniques of formal verification to a variety of industrial applications, and this is why he straddles the section on the Market and the section on Formalism. In this paper, Lamport claims that high Level Specifications, such as the tools provided by his TLA+ language are essential to verifying industrial systems, concurrent algorithms, and more.

TLA+ allows you to provide specifications which get “compiled” into proofs. In many ways, I feel that in the long run his work on TLA+, which makes proving systems more accessible, will be of great importance. I’ve seen mention of it being used at Amazon, for example, and in other industrial modern applications. It shows that Lamport has made the connection between the theory of distributed systems and one form of its practice, although a form of practice that is very different from what most of us do.

Another luminary in the field of distributed systems, Ken Birman, has had quite a bit to say over the years about the mixture of commercialism and research and its impact on practitioners. Birman is noted for his work on Virtual Synchrony and the Isis toolkit, which is very well covered by his own bit of archaeological work in 2010’s A History of the Virtual Synchrony Replication Model.

Virtual synchrony is a system for considering work in distributed systems and has had various formulations over the years. Birman’s flirtations with industrial application of distributed systems are storied - his work was used by the New York Stock Exchange, amongst other important clients, for many years. Additionally he is an outspoken, reflective writer who has participated in workshops and produced papers about the history and impact of distributed systems research.

To get a better sense of Birman’s involvement in industry, a famous exchange in the form of academic papers from 1993 between Birman and two other authors in the field, Cheriton and Skeen, can and should be consumed by fellow archaeologists. Cheriton and Skeen came out with Understanding the Limitations of Causally and Totally Ordered Communication, which Birman claimed was a thinly veiled attack against his work on Isis in A Response to Cheriton and Skeen’s Criticism of Causal and Totally Ordered Communication.

The interesting aspect of this exchange is that Birman indicts Cheriton and Skeen for having financial skin in the game, and for over-simplifying his work in order to prove a relatively lame point. Fascinating reading, and important in that it reminds us that researchers are living, breathing human beings who have to survive and want to advance their ideas.

Fast forward to the mid 2000’s and two more documents that have Birman’s name on them, 2006’s How the Hidden Hand Shapes the Market for Software Reliability, and 2008’s Towards a Cloud-Computing Research Agenda both contain critical looks at practitioners, researchers, and the market in general. In these works Birman urges his fellow researchers to pursue practical and thus humane solutions to the problems that actual people face. He has many interesting things to say, from the impact of the “impossibility” idea I discussed above to the blow that the applicability of transactions and database theory had on the field of software reliability.

Overall, however, the take away from his work is that we need to be aware of the impact that the market has on our work, and thus our lives.

To end the section on the market, I wanted to briefly touch on a phenomenon that has had a prolific impact on the theory and practice of distributed computing that is a direct result of commercialism: modern industrial research, such as the work produced at Google and Microsoft.

Google’s papers in particular have been crucial to the field and many practitioners who I spoke to in preparing for this talk point directly to these papers as the initial sources of interest and access for them. Here you have companies at a scale that most people will never see actually publishing the techniques they use to do the seemingly impossible.

This feedback loop between large companies and academia is seen by some as a mixed blessing, however. If the deep academic work pursued by some is considered inapplicable, how could the average practitioner ever hope to leverage the lessons of a company who counts synchronizing atomic clocks between international data centers among its problem areas?

The answer is that sometimes they are applicable, and sometimes they aren’t, and as usual it is up to the practitioner, who often has no training, to make this determination.

Okay, that was a lot. Now that I’ve covered each of the three threads, and exposed a few obvious sources of tension for the modern practitioner, I have two recommendations in the form of directions for the community to pursue: Language, and Humanity.

Programming Languages

In pursuing my archaeological project, I came across many many “languages for distributed computation,” and I also know of some interesting work going on right now in this field. However the idea that a “language for distributed computing” that isn’t Erlang could possibly exist is not known to many developers, and I think it is high time to destroy this myth.

Two books that I have been very fond of lately that are directly applicable to why I feel that it is important for researchers and practitioners to pursue the advancement of languages for distributed computation are Van Roy and Haridi’s Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming and Carlos Varela’s Programming Distributed Computing Systems: A Foundational Approach.

Concepts, Techniques and Models, also known as CTM, and its accompanying whitepaper Teaching Programming With The Kernel Language Approach is a revolutionary Computer Science textbook that completely changed my brain and finally got me to understand the connection between comptuer programming and computer science, no easy task to be sure - just ask Dijkstra, or anyone unfortunate enough to work with me.

In the paper, Van Roy and Haridi state that Teaching programming in terms of a single paradigm or language has a detrimental effect on programmer competence and thus on program quality …and that is indeed how many practitioners are taught. They are taught to bend the will of the languages that are commercially popular to the needs of distributed computing at the same time that they are expected to learn the foundations of the problems themselves. This is catastrophic.

CTM is an important book for many reasons, chief amongst them being that it makes the reader realize that small, simple, understandable languages and formal models that can be evolved into more complex ones are very powerful for forming intuitions of problems in computer science. In the book you are exposed to a basic language with a simple underlying formal model that is made more and less advanced over time as various subjects are treated - state is added here and taken away, distribution is included when it is needed, etc.

Carlos Varela is an author who is clearly inspired by Van Roy and Haridi’s work, and his excellent book on distributed computation takes the position that understanding concurrent computation is essential to understanding distributed computation, and proceeds to elucidate various modern formal process calculi that he argues should be the basis for future languages.

Varela describes the terms distribution and mobility as essential properties for distributed models. Distribution is the idea that computation can occur in different locations and mobility is the idea that computation can move between these locations. The combination of distribution and mobility is what most modern developers are actually dealing with, but they simply do not have these tools.

In other words, from both Van Roy and Haridi and Varela’s work we can take the lessons that languages devoted to distribution are necessary to teach the concepts of distribution, and that there is great potential in formal models that encode the ideas of distribution and mobility that have not yet been directly applied in the operational semantics of a programming language.

Humanity

The most fruitful work that we have achieved in the field of Computer Science is a direct result of the application of resources towards the ends of furthering and better understanding humanity. It is a simple fact that the longer we ignore this reality, the more it is to our peril.

Two papers will end this talk. The first is On Proof and Progress in Mathematics by the mathematician William Thurston. I came across this paper when Thurston died and it was recommended to me by many smart people on the internet, which is the way that I discover most of the interesting things that I read. I wasn’t sure what to expect but I certainly wasn’t prepared. This paper is an absolute brain-breaking work of painful beauty, and I won’t say much about it besides the fact that everyone here should read it, and that it contains keys to the questions I’m trying to bring to your attention in this talk. As a short summary, however, Thurston deals with the idea that “progress” in mathematics is often measured by proof, and attempts to understand the impact that it has. Section 4 “What is a proof,” in particular also has direct applicability to computer science researchers and practitioners because of Thurston’s fondness for technology - he often integrated computers into his proofs.

Lastly, a paper that I learned about very recently, Papadamitriou’s Database metatheory: asking the big queries hits on many of the notes that I’ve brought up here in a much deeper and more intelligent way. The author discusses the impact of the definition of the field by negative proof and compare’s Kuhn’s theory of revolutions in natural sciences to Computer Science - definitely a worthwhile read. Papadamitriou’s attempts to understand and contextualize the work done by researchers at various points in innovation cycles is a poignant reminder that our place in time impacts what we do and how effectively we do it.

In Conclusion

Given all of the lessons above, my hopes for the future can be summed up as follows:

-

Practitioners: To the best of your ability, recognize the formalisms your work is based on, understand the details of the papers you’re reading, and be careful with how you communicate these ideas to your peers.

-

Academics: Guide the community and strike a balance between alleviating current pain and making the future path clear.

-

Industrial Researchers: Provide complete implementation details in papers, be generous with your Open Source contributions, try to give advice directly to practitioners.

In conclusion, distributed systems is an incredibly deep and rich field. Studying it has been absolutely thrilling and in addition to a fascinating body of artifacts that are ripe for more archaeological work, the community is generous, motivated, and forward-thinking.

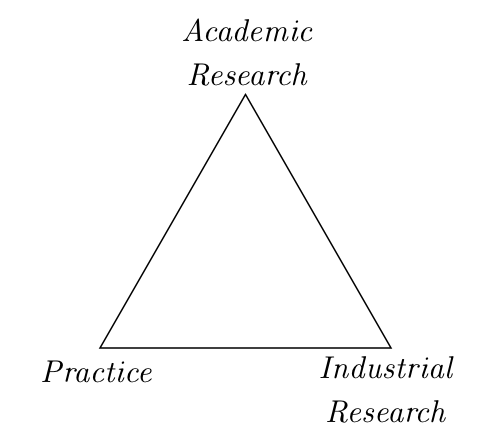

I hope this talk inspires you to be reflective about the challenges of programming and understanding distributed systems regardless of your position in the “triangle” above, and remember, together we can do some amazing things.