# #

Distributed Systems Archaeology, Part One

This post presents the first part of a narrative form of the talk I gave at Ricon West 2013. The works cited can be found here, and the slides can be found here. Video is forthcoming.

Introduction

My name is Michael Bernstein, and I’m Obsessed. Not with anything in particular, just in general.

This talk is called “Distributed Systems Archaeology,” a phrase I designed to be a catchy talk title before actually thinking through what it meant. The more I thought about it, however, the more I convinced myself that it had meaning, and so here we are.

If Archaeology is “the study of human history through the artifacts,” then “Distributed Systems Archaeology” is an attempt to apply an artifact-driven approach to understanding the history of the field of Distributed Systems.

Why would I want to do that?

In order to understand that you’d have to know more than you want to know about me, so I won’t say more than this: during the course of my career as a programmer at startups, I have found it impossible to avoid interacting with and producing distributed systems. They’re everywhere.

In addition to their overwhelming ubiquity, I also found reasoning about distributed systems very difficult. I didn’t understand how the tools worked or even what tools existed, and even worse, no one around me really had any more experience than I did in the matter.

To top it off, the resources available to people in my position, which are practitioners who are trying to help build small companies and turn them into medium sized and hopefully giant companies, are scant.

There were some merciful exceptions, like Jeff Hodges’ Notes on Distributed Systems For Young bloods, which begins with this quote:

“I’ve been thinking about the lessons that distributed systems engineers learn on the job.”

I read that and thought, “well shit, I’ve been thinking a lot about that too!” In this essay Hodges states that while developers will come across literature, they will not come across applicable lessons. This was my experience, and this delta, between the literature and the lessons is what I am trying to understand.

So I saturated myself in the literature in order to get some clarity around what the field was all about, and why it is so challenging to interact with distributed systems precisely at a time when we need them to be easy.

To help answer this question, I started out by searching for lists of classic papers and books, reaching out to experts, and absorbing as much as I could. As I started to get a sense for the field, I started to recognize some common threads as I traced the influences and trends.

I’m going to use these threads to tell a story about three influences on the field of distributed systems research and practice:

- The Mind

- The Proof

- The Market

Each of these categories represents a common thread that I have traced through the literature, and each of these threads contained information and wisdom that helped me understand where we started, and how we got to where we are today.

The Mind: Artificial Intelligence

The roots of distributed systems research in artificial intelligence

First, the mind. Around the time I pitched this talk, I was heavily influenced by trawling through the archives of the AI Group at MIT, particularly the insanely rich and amazing group of documents known as the “AI Memos.” Amongst these memos there are papers by many of my intellectual heroes, dealing with a very wide range of topics. Since the origins of the research funding for computer research was heavily based in Artificial Intelligence, it makes sense that some of the most forward thinking research and thought at the time was coming out of this laboratory.

AI researchers had access to hardware and also the freedom to dream about what the future of hardware and software, and how they interact, would look like. AI had a heavy influence on the origins of distributed systems and provided the breeding ground for some of its brightest thinkers.

My dream history of distributed systems starts a very long time ago (I’m going to publish an extended bibliography), but for the sake of time, I’ve chosen to focus on three sources: Licklider, Minsky, and Hewitt. Their works is fundamental to the field of artificial intelligence, and in my estimation, to distributed systems.

Licklider and Minsky each contributed massive amounts of energy and numerous novel ideas to the field of artificial intelligence and computer science in general, helping to provide the foundation for the very definition of hackers, software, networks, the internet, and more.

One of the best anecdotes about Licklider I’ve heard came from an interview I watched with Tracy Licklider, JCR Licklider’s son. According to Tracy, Licklider was an eccentric. He did eccentric things like drink Coke for breakfast. He did eccentric things like dreaming about connecting the entire human race and abolishing the barriers to knowledge inherent in an unbalanced society. He also did eccentric things like calling that project the Intergalactic Computer Network because he knew the scientists he was pitching to would think it was funny.

Licklider spoke of Man-Computer Symbiosis and truly believed in the distributed future.

His The Computer as a Communication Device was a futuristic take on technology. Licklider spread money around to big thinkers, started programs, and believed, above all, in humanity.

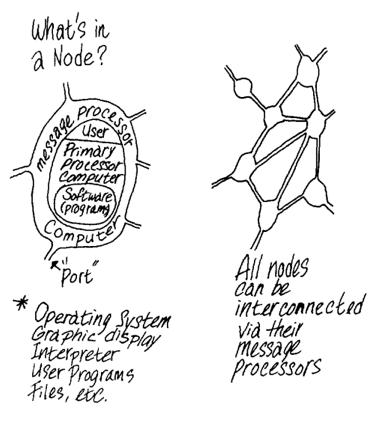

Here is an image from “The computer as a communication device” where Licklider is trying to work out how information could travel through networks. We see terms like “nodes,” “ports,” “message processor.” He is using biology as an inspiration for modeling the flow of information:

Among the programs that Licklider helped to fund was project MAC at MIT, where Minsky was a teacher and Carl Hewitt was a student. Minsky’s interests were oriented toward understand humanity as well - his obsession was the brain and the mind. Minsky pushed the Artificial Intelligence agenda and inspired the use of computers to help understand and extend the human experience.

In 1970 he published the 1968-1969 Progress Report which covers the depth of the work going on at the MIT lab at the time. Work began to transition from purely theoretical, to implementation based, and back. The primary concern was understanding how computers and humans could interact. This brief summary does Minsky no justice - please read about him to discover more.

Carl Hewitt’s work is an inflection point for me in the history of distributed systems and his ideas are familiar to many of the people at this conference even if they don’t know it.

In 1973 he published A Universal Modular ACTOR Formalism for Artificial Intelligence which defined the Actor model of Computation and discussed his language PLANNER. The actor model describes computation as being performed by a single kind of object, known as an actor.

Actors have simple rules which allow them to perform general purpose computations, and because of the loosely coupled nature their definition and implementation, they can be inherently distributed.

In 1976 Hewitt published a paper, Viewing Control Structures as Patterns of Passing Messages (A.I. memo #410) which discussed the work he had done up to that point with the actor model and message passing. Although there were several technical achievements being pursued and accomplished, the work Hewitt was doing was still primarily framed in human terms - “Modelling an intelligent person” and “Modeling a society of experts” are both stated goals early on in the paper.

The actor model turned out to be one of the most enduring ideas produced from the work done on AI at MIT. Modern programming languages like Erlang have a semantics that is based on the actor model, which has been formalized several times. Hewitt’s work is an inflection point for me in the history of distributed systems because of how implementation based it is - there is formalism, there is code, there is hardware.

To recap, Licklider, Minsky, and Hewitt all were inherently concerned with the distributed nature of knowledge and how technology could be used to solve a wide variety of problems. The origins of the field of distributed systems can be found here, at the very intersection of technology and humanity.

Next, we will look at ‘Formalism: The role of the proof the history of distributed systems research. Stay tuned.